In Madagascar, Conservation and the Art of Saving Our Natural World

Roberta Kravette, Co-Founder Destination: Wildlife

Madagascar in Three Fast Facts and a Question

Fact 1. Isolated for tens of millions of years, the world’s 5th largest island, Madagascar, is a biodiversity hotspot.

Fact 2. More than 90% of its flora and fauna are endemic; much of it, including 103 of 107(!) lemur species, is threatened, endangered, or critically endangered.

Fact 3. 75% of its 30.3 million people live below the Malagasy poverty line of 4,000 ariary/day (less than one dollar), according to the World Bank 2023.

And the question:

How Do You Preserve Biodiversity, while Empowering and Enhancing the Well-being of People?

Two Young Biodiversity Conservationists Have a Creative Idea

Johanna Mitra of New York City and Alain Rasolo of Ranomafana, Madagascar, believe that art is one answer - and they are proving it with oloNala, the New York-based nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization they founded. The organization’s focus is on “uniting local artists, scientists, and educators … to develop innovative biodiversity conservation solutions.” The first test of oloNala’s promise is located in Ranomafana, Madagascar, but the pair envision the system working for biodiversity hotspots worldwide.

I met Johanna and Alain at the Explorers Club headquarters in New York City for the Safina Center’s Annual celebration. Alain is a Safina Center Junior Fellow. My good friend and fellow Explorer, Rhonda Stein, introduced us; she “discovered” them while working with the Centre ValBio in Madagascar, where Johanna was the Communications Officer and Alain was the Artist in Residence.

Both trained in biodiversity conservation, Johanna Mitra, an MBA candidate, and Alain Rasolo, artist and the organization’s Director, created oloNala to educate and inspire a personal connection to nature through art. The Goal: Preserve and protect biodiversity and enhance the well-being of the people. Image: Thanks to Johanna Mitra

Smiles are what you notice first about Johanna and Rasolo (his preferred moniker), smiles, and a quiet self-assurance without any hint of arrogance, coupled with a sense of excitement that seems ready to bubble out at the least opportunity. They are young and enthusiastic, but perhaps because each has seen more than their years imply, they are centered and clear-eyed about the herculean challenges we face in protecting the planet’s biodiversity and uplifting its people. Alain and Johanna are not talking about helping the world. They are doing it.

✍︎ The following are excerpts from our conversation:

Art As a Catalyst for Healthy Forests and People

The canopy at the newly (2019) discovered Ivohiboro (the Lost Forest) Rainforest. Drawing: Alian Rosalo.

What is oloNala? What inspired its Creation?

Rasolo: oloNala, comes from the Malagasy words “olo”, meaning people, and “ala”, meaning forests. I think “people and forests” summed up our community-based approach to conservation. You can’t have healthy communities without healthy forests, and it comes down to people to protect the natural environments that we and countless other species rely on.

oloNala’s Guiding Principle: Humans and nature must coexist in harmony for sustainable progress.

The Secret Recipe: Environmental Education, Art and Storytelling

Johanna: We also felt oloNala would be the best way to combine the things that we both know and love, and in ways that can help support the already fantastic conservation work being done in Madagascar. Rasolo and I both have an academic background in biodiversity conservation, and between us, a shared interest in environmental education, art, and storytelling. We channel that through oloNala by collaborating with Malagasy teachers, community members, and artists who see art's value in educating and creating a shared and culturally relevant narrative around the importance of preserving biodiversity.

How Do You See oloNala Helping to Solve Madagascar’s Conservation Challenges?

Rasolo: Well, being Malagasy means basking in the island’s natural wonders—the dramatic landscapes and the unique and endemic lemurs, birds, reptiles, and insects. But it also means confronting the numerous challenges facing our biodiversity today, including forest loss, climate change, and wildlife trafficking. These are challenges that impact us, too, as people. It’s only natural that our first step is to try to inspire change on a local scale.

We think that oloNala’s approaches to tackling Madagascar’s conservation challenges — incorporating and embracing artistic expression as a means of communicating, relating to, and inspiring action towards these challenges- will bring a breath of fresh air to the different efforts that are already underway in the country and hopefully inspire new ones in the future.

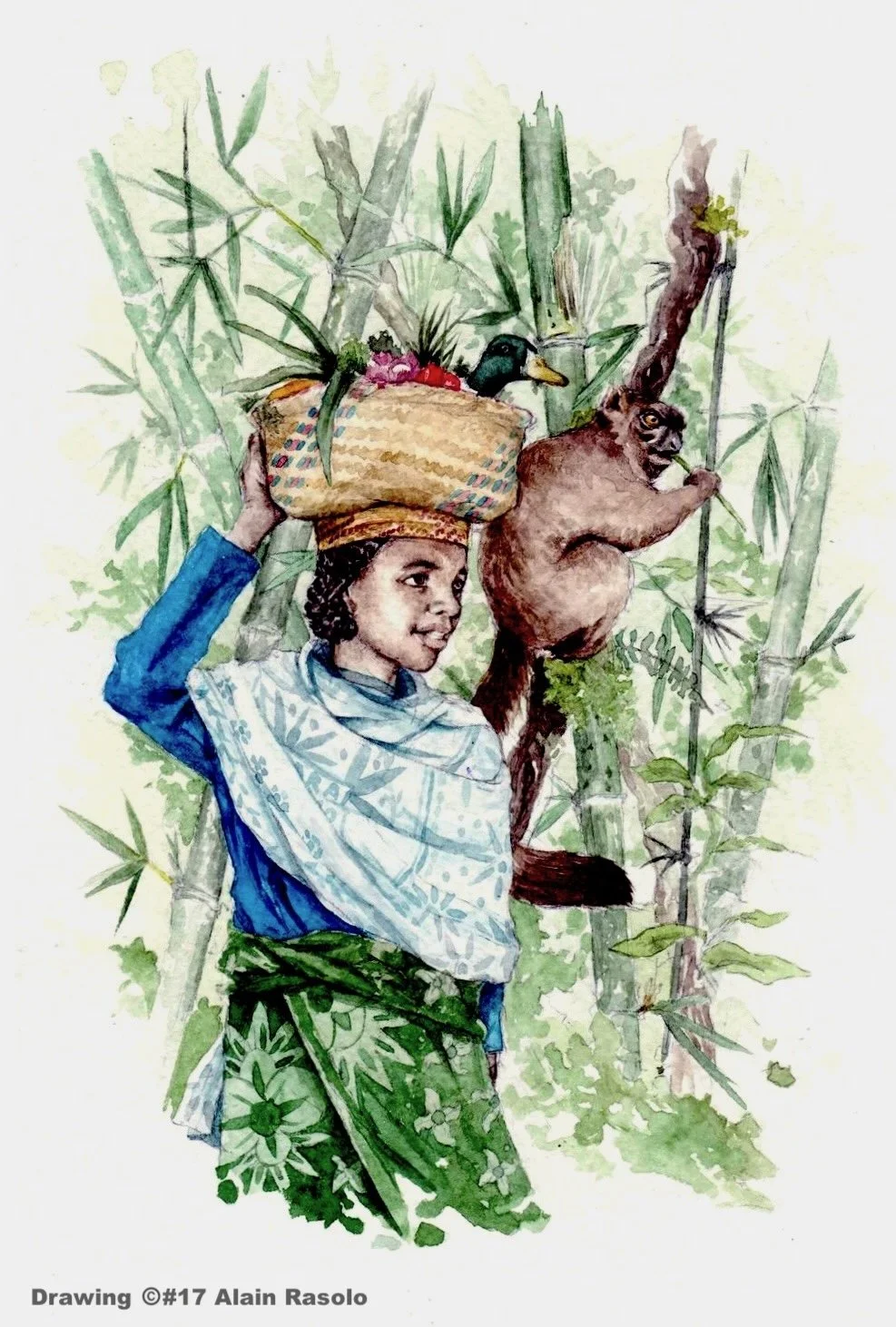

Critically endangered Golden Bamboo Lemur (or bokombolomena or varibolomena) is able to ingest 12x as much cyanide as would be lethal in another species of its size. Drawing: ©️Alain Rasolo

Creativity That Inspires Connection and A Sense of Responsibility

✍︎ You talk about achieving conservation through creative solutions. “Creativity” does not necessarily mean art. When did you realize there could be a connection between creativity and conservation?

Johanna: I think the complexity of the issues facing local communities, biodiversity, and the ecosystems they exist within can’t always be solved within the dominant and oftentimes rigid practices of conservation ‘science’. So, to me, incorporating creativity into conservation means embracing and supporting the ideas and initiatives of the communities with the closest ties to and the largest stakes in the conservation of their environment.

Rasolo: As an artist myself, I’ve witnessed firsthand the effectiveness of embracing a creative approach. We often say that “We protect what we love,” and in that regard, art and the emotions it can evoke, especially when combined with people’s own experiences studying, relying on, or living in nature, can have the effect of inspiring connection and a sense of responsibility toward its protection.

✍︎ This is a belief we at Destination: Wildlife hold very strongly, that sustainable conservation is in the hands of the local people. Without love for the environment, there is no hope for preserving its biodiversity. We agree, art can form the connection, and the connection becomes love.

oloNala, Creating Connections through Nature Journaling.

Says Johanna: Whether helping teachers engage their students in environmental science or nature illustration through trips to the forest, or connecting Malagasy artists with scientists to co-produce artwork and outreach materials — these are the ways oloNala aims to join creativity and conservation.

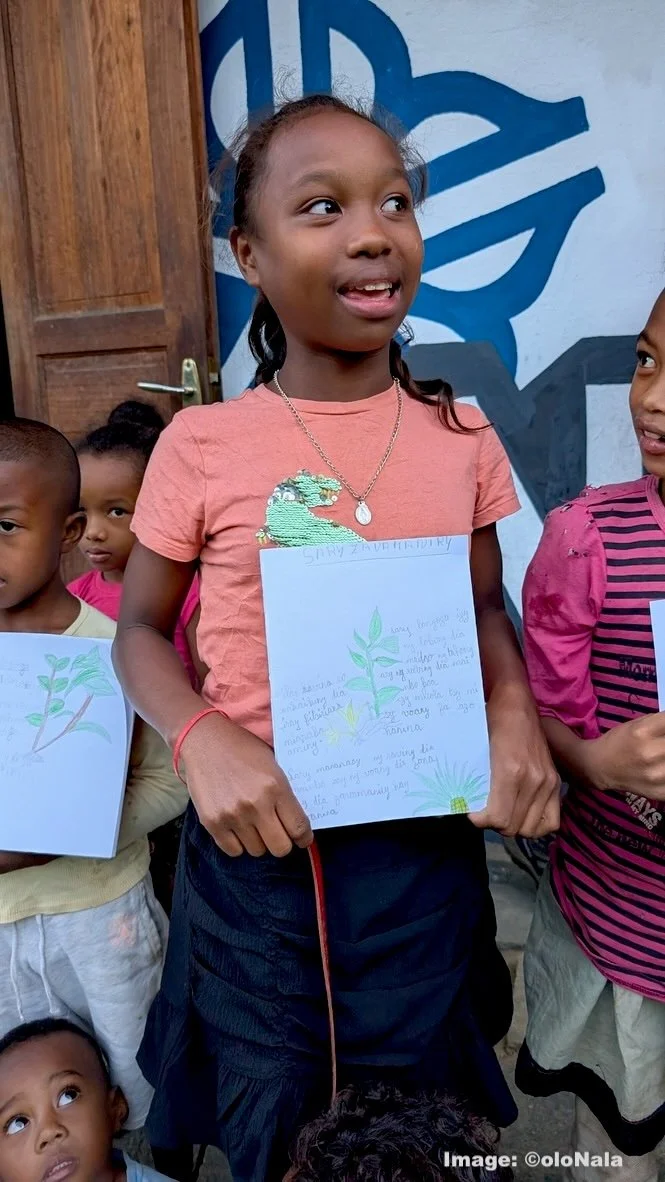

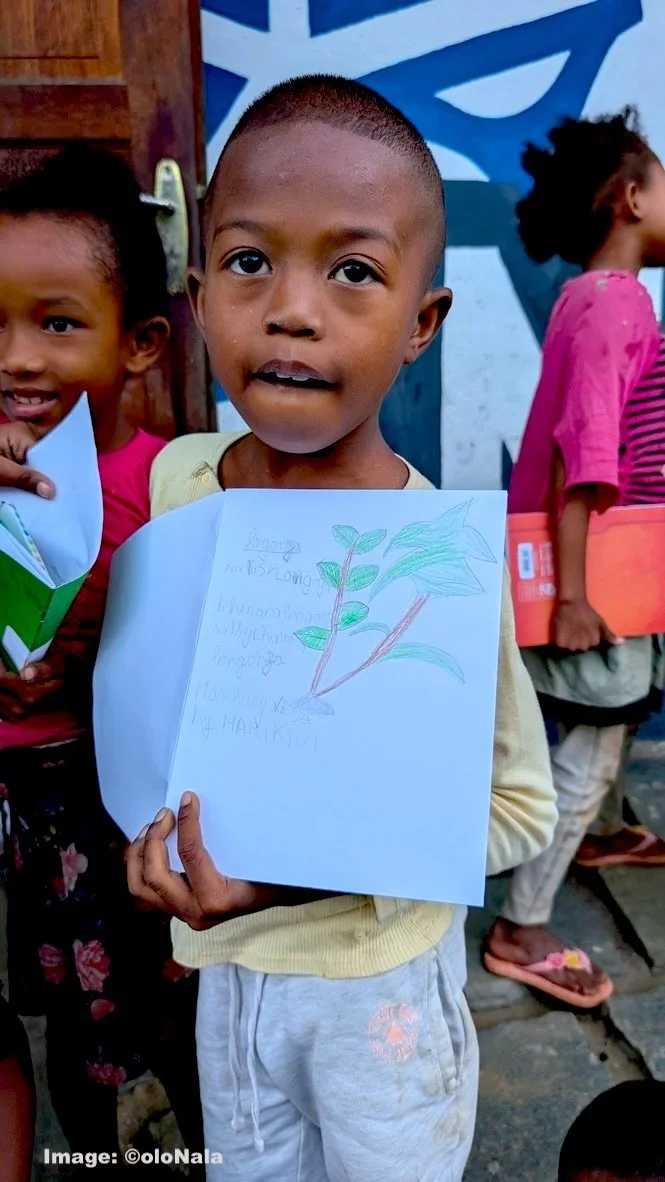

Johanna: We’ll be starting right in the heart of Ranomafana, at the local Nature Center. Together with the teachers there, we’re starting to incorporate nature journaling into their ongoing environmental education programs. The students are provided with art supplies and journaling prompts in Malagasy, with which they can collect observations, make drawings, and ask questions about the natural world. Then, they’ll be able to showcase their work amongst their peers and the community.

This practice not only helps grow the students’ awareness and appreciation for the natural world but also helps them build self-confidence, critical thinking, and observation skills. Plus, it provides the students with a fun, creative outlet. I’m really looking forward to seeing where their curiosity takes them.

Rasolo: As oloNala grows, we’ll be expanding on my previous work with the VOI association in Ranomafana. Our support will be done on a small scale first, trying to maximize impact by financially supporting projects they propose that address their most pressing needs. And then, of course, construction for the Art Residency is underway. The sooner we can get the program up and running, the better!

Johanna: We’re both really excited to keep building oloNala and bring more attention to Malagasy-led conservation, education, and art projects. Investing in the community’s efforts is the most effective way to achieve conservation outcomes that best support people and the environment.

Creativity and Conservation: The oloNala Artist Residency

✍︎ Tell Us About the oloNala Artist Residency.

Rasolo: Becoming a professional Malagasy artist and more particularly, a wildlife artist, is neither an obvious nor an easy path, not least because making a successful living as a visual artist in Madagascar is generally viewed as extremely difficult. Additionally, art in the Malagasy conservation world is vastly unexplored by local talented artists. Even for me, my career came from a fruit of love for art, nurtured by the help of fortunate connections, and supported by people who believed in my talent.

But as one of the few Malagasy artists in this field, I’m deeply motivated to give the same opportunities to other Malagasy artists, with the hope of letting Madagascar’s beauty inspire them, but also supporting them in creating a viable and meaningful career. The Artist Residency is a project that is really dear to both of us, and we’re currently working on constructing the studio space for the residence itself. We look forward to hosting our first residents once it’s completed.

The Centre ValBio Connection

* The Centre ValBio research station (CVB) is dedicated to the conservation of Madagascar's “unique and biologically rich ecosystems.” Founded in 1986 and located in Ranomafana, Madagascar, the CVB is led by renowned primatologist Patricia Wright.

✍︎ You both worked with the research institute Centre ValBio in Ranomafana, Madagascar, and its founder, Dr. Patricia Wright, before creating oloNala. What were you doing there and how did you meet?

Rasolo: I’ve been the artist-in-residence at Centre ValBio since 2015, at Patricia’s invitation. I often work with the Centre’s Education Team to develop posters and other educational materials to distribute at local schools, as well as helping with the graphic design of their annual report. We met through working on this project actually— Johanna came to Madagascar in early 2023 and was working on the report alongside me.

Johanna: Yes, I had just joined the Centre as their Communications Officer. Patricia had been my professor during my last year of undergrad at Stony Brook University, so I’d been volunteering in her lab on campus before she invited me to come to Centre ValBio. And since Rasolo was also a Fellow at The Safina Center at the time, he had the opportunity to come to New York City twice, where I live, and that’s when we were able to really start developing oloNala as a nonprofit.

The Safina Center Connection

✍︎ Alain, tell us a bit about your connection to The Safina Center. How do you see your missions overlapping?

Rasolo: Prior to and as a Fellow at the Safina Center, my work aligned perfectly with the Center’s mission: “Advancing the case for life on earth.” I invested part of my fellowship in projects that aim to support Ranomafana’s National Park and the surrounding forest, which is managed by the local community, by providing creative materials, like signs, logos, entrance tickets, and pamphlets. Now, as an alumnus, I aspire to continue that mission through oloNala, to bring up the value of the rainforest and all the living things within and depending on it, wildlife and humans alike.

It’s A Small World,

How Woolly Monkeys in Colombia Brought oloNala to Life in Madagascar

✍︎ And Johanna, you were an alternate candidate for a Fulbright Award for your research proposal, “Evaluating Rehabilitation and Reintroduction Effects on Woolly Monkeys in Colombia.” – what brought your interest from Colombia to Madagascar?

Johanna: Funnily enough, it was actually Madagascar that sparked my interest in Colombia! While in Madagascar, I accompanied a team from Centre ValBio on a translocation project involving greater bamboo lemurs, a critically endangered species. I grew interested in understanding how translocation success rates can be improved, and particularly for primates. That led me to apply for a Fulbright to study woolly monkeys that had been rescued from wildlife trafficking, rehabilitated to learn natural behaviors, and released into protected areas in Colombia. My proposal also incorporated collaborating with local ranchers and forest rangers on engaging visiting school groups in bilingual lessons in ecology and the importance of primate conservation.

The outreach aspect of the project was something I really wanted to emphasize with oloNala, as conservation never happens in isolation from human communities. I’ve seen this in Ranomafana firsthand. So many of the local teachers, nature guides, and community members are dedicated to engaging people of all ages, from all backgrounds, in understanding the ecological, cultural, and social value of Madagascar’s wildlife and landscapes. I think if we can help expand their reach through oloNala even just a little, it still goes a long way.

More About Alain Rasolo and Johanna Mitra

Johanna and Rasolo at the Explorers Club in New York City for the 2024 Safina Center Annual Celebration.

Alain Rasolo, Director of oloNala was born in Madagascar and lives in Ranomafana. Rasolo, a self-taught wildlife illustrator and graphic designer, discovered his love (and talent) for art on a field trip for his License degree in Biodiversity Conservation and Environment in Tampolo, a protected area in Toamasina, Madagascar. Alain creates outreach and educational materials for several conservation and education organizations. He is the artist in residence at Centre ValBio, and part of the Junior Fellows Network at the Safina Center.

Stay in Touch with Alain Rasolo: To see more of Rasolo’s wonderful conservation artwork, follow him on Instagram @alainrasoloart

Johanna Mitra is a Master's student studying International Nature Conservation at the University of Göttingen, Germany, and an MBA Candidate at the Quantic School of Business and Technology. Johanna’s concern for the Earth, its people, and social justice has led her to volunteer positions at New York’s Wild Bird Fund and TEAM TLC NY, assisting refugees and asylum seekers. After our weekend in New York, Johanna moved to New Zealand, where she is working on her Master’s at Lincoln University and volunteering at Toho Indigenous Analytics, a social enterprise for environmental and social justice in her spare time.

Stay in touch with Johanna Mitra: LinkedIn

Follow oloNala on Instagram @olonala.inc

✍︎ In a time when just about all the news we see or hear is disheartening, Alain and Johanna give me hope for a better world.

Your donation helps oloNala support community art and conservation projects at The Ranomafana Nature Center, VOI Mitsinjo, the Art Residency Program, and more.